JavaScript is the programming language of the web.

HTML and CSS are the structure and visual appearance of a website. JavaScript offers the ability to turn these static web pages into dynamic, interactive experiences. As you proceed through your work as a designer, understanding JavaScript and programming in general is beneficial to bringing your design concepts to fruition on digital platforms.

JavaScript’s History

JavaScript was developed in 1995 by Brendan Eich while working at Netscape Communications Corporation. During this time, the internet was still in its infancy, and most web pages were static and lacking in interactive features. Netscape recognized these limitations and tasked Eich with creating a language that would complement HTML and CSS.

Although the language was created under time constraints – it took Eich merely ten days to develop the initial prototype – JavaScript had an immediate impact.

But first, HyperCard

Before diving deeper into JavaScript, it’s worthwhile to acknowledge the influence of HyperCard, a software tool developed by Apple in 1987. HyperCard introduced many people to programming through its graphical interface and “stacks” of cards, which could contain text, images, and interactive buttons. In many ways, HyperCard served as an early model for the web, offering a user-friendly platform where people could create software applications without extensive coding knowledge.

HyperTalk was the scripting language for HyperCard. Although it was designed in a very different context, its intent—like JavaScript’s—is to enable interactivity and functionality. To illustrate their similarities and differences, let’s consider a simple example, a clickable button that updates a piece of text when clicked:

on mouseUp

put "Clicked!" into field "Output"

end mouseUp

Later on, you’ll see just how similar this is to JavaScript. Back to the 90s.

The Browser Wars

Netscape Navigator and Microsoft’s Internet Explorer were the key players in the web browser market in the late ’90s. This period saw intense competition between the two companies, commonly referred to as the “Browser Wars.” Each company was keen on incorporating unique features to lure users, and JavaScript became a critical part of this competitive landscape.

While the Browser Wars accelerated the development of new features, they also led to a fragmented web landscape where different browsers had varying levels of support for JavaScript features. This inconsistency made it challenging for developers and designers alike to create web experiences that were universally accessible.

The discrepancies in JavaScript’s implementation led to the necessity for standardization. ECMAScript, first published in 1997, served this purpose by providing a set of standardized guidelines for JavaScript. This initiative by the European Computer Manufacturers Association (ECMA) aimed to ensure that the language’s core functionalities remained consistent across different browsers and platforms.

Subsequent versions of ECMAScript have introduced new features, like asynchronous programming and arrow functions, that make the language more powerful and easier to use. These updates continue to expand the possibilities for what can be achieved in both design and development.

Contemporary JavaScript

Fast-forward to the present, and JavaScript has become an omnipresent force in web development. It is not limited to just client-side scripting; server-side environments like Node.js have extended its utility to back-end development. Libraries and frameworks such as React, Angular, and Vue.js (which power Facebook, Airbnb, Adobe, just to name a few) further simplify complex tasks, enabling the creation of more sophisticated web applications.

Front-end vs. Back-end

In discourse around JavaScript you will likely have heard the terms “front-end” vs “back-end”. Front-end development focuses on what users see and interact with in their browser. This is where JavaScript originally made its mark, offering the tools to create interactive and dynamic user interfaces.

Back-end development deals with the server-side operations that power a website, from databases to application logic. JavaScript’s utility has expanded to this realm as well, but for a long time it could not function in this capacity. We will be exploring JavaScript in a front-end context.

Hooking up JavaScript

JavaScript can be included in an HTML document in a few different ways. The most common (and the only way I suggest you to use) is to use a <script> tag, which can be placed in the <head> or <body> of your document. The <script> tag can either contain JavaScript code directly, or reference an external JavaScript file. The latter is the preferred method, as it keeps your HTML and JavaScript separate, making your code easier to maintain and debug.

<body>

<h1>Hello, world!</h1>

<!-- site content -->

<!-- JavaScript goes right before end of body tag -->

<script src="script.js"></script>

</body>

Programming Languages

Here is a great passage about programming languages from a fellow Parsons instructor, Eric Li:

At its core, a programming language tells a computer what to do, exactly how you want to do it. In order to understand what we can do with programming:

- We need to learn what computers can and can’t do

- We need to learn a programming language: JavaScript

As I’ve said before, a computer is nothing more than a fancy calculator which can do things millions of times a second. In order to tell it what to do, what are our options?

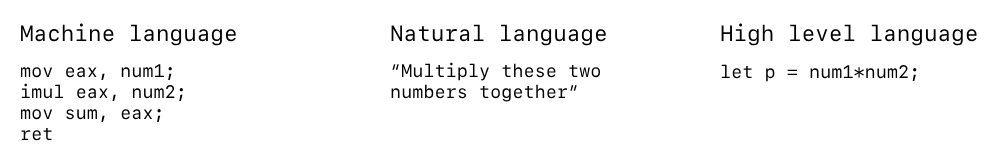

Machine language is great for telling the computer exactly what we want it to do. But as you can see, it’s very tedious and super easy for humans to make mistakes.

A natural language like English may seem ideal, until we realize that it’s hard to be specific enough for a machine to correctly interpet. In the above statement, the machine has no idea which numbers we’re referring to, or where to put the product.

High-level languages are a good compromise. It is a bit harder to read than natural language, but significantly easier than machine language. And it has enough specificity for a computer as well!

Data

The most base-level part of JavaScript is data. Data comes in a few different types:

Primitive Data Types

Think of primitive types as simple, basic types of data. Each variable that holds a primitive type stores the actual value. Here are some examples:

| Type | Explanation | Example |

|---|---|---|

| Numbers | Basic numeric values | 5, 3.14 |

| Strings | Bits of text surrounded by quotes | "hello" |

| Booleans | Can only be true or false |

true, false |

| null | Represents no value | null |

| undefined | Indicates a variable has not been assigned a value | undefined |

If you change a primitive data type’s value, you’re creating a new piece of data; you’re not altering the original one.

Variables and Values

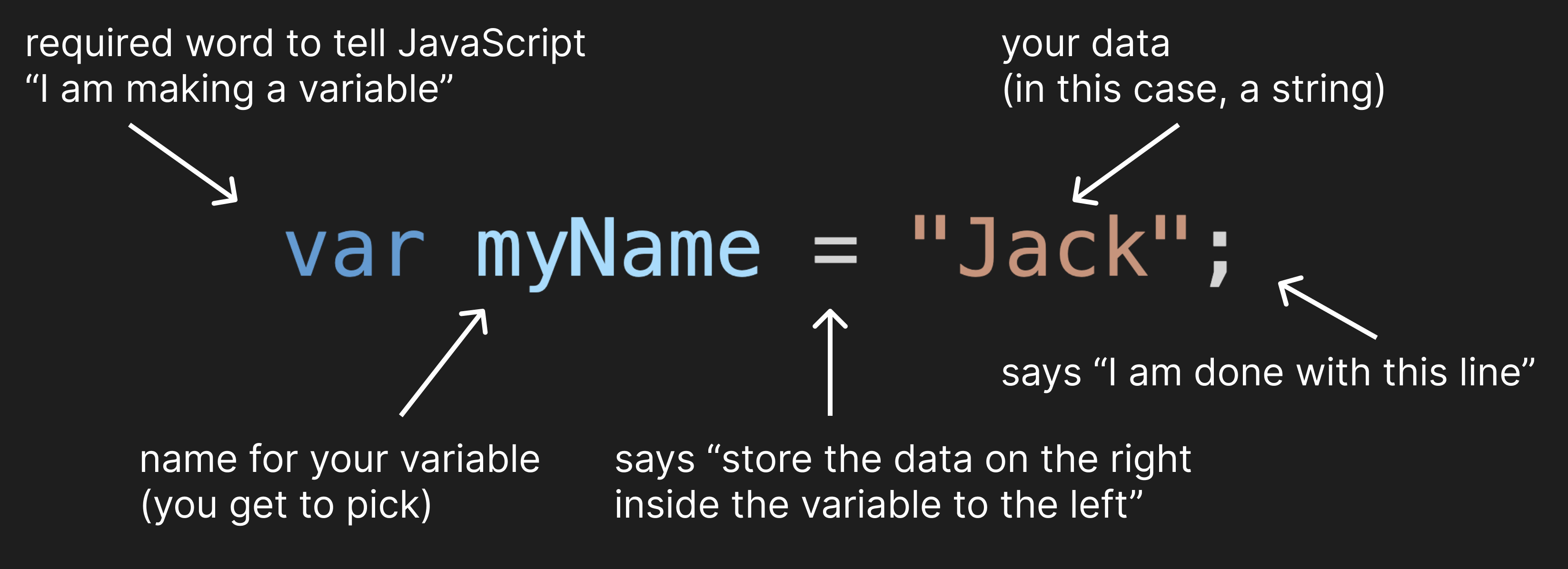

Variables are containers for storing this data. They can hold these different types of data, such as numbers, strings, arrays, objects, and even other functions.

One equals sign is used for variable assignment. You can think of it as “is” or “gets”. For example, var myName = "Jack" can be read as “the variable myName gets the value Jack” or “the value Jack is stored in the variable myName”.

The way you declare a variable can also affect your code. While var was traditionally used for variable declarations, it has largely been replaced by let and const due to scope and hoisting issues. The difference between them is a little out of scope for this class, and I don’t care which one you use.

Higher level data types

Arrays and objects are higher-level data types that can store multiple values. Arrays are ordered (1, 2, 3, etc.) lists of values, while objects are unordered collections of key-value pairs (the key is on the left, and the value is on the right). You can think of objects kind of like a variable with more variables inside of it.

Arrays

Arrays hold a list of values in order. You create an array using square brackets [] and can put values inside, separated by commas. You can access these values by their position in the list, starting from 0.

var colors = ["red", "green", "blue"];

var mixedArray = [1, "two", true];

If you want a value from the array, you access it with “index notation”:

colors[0] // this would give you the first thing in the colors array, which is "red"

colors[1] // "green"

colors[2] // "blue"

Objects

Objects store multiple pieces of data together. When you create an object, you use curly braces {} and add data inside. Each piece of data in an object has a name followed by a colon and the value. This name is called a “key,” and the value can be any type of data.

var person = {

name: "Alice",

age: 30,

isStudent: false

};

Objects actually have two syntaxes for how to access the data inside, in contrast to Arrays which only have one. There’s “dot notation” and “bracket notation”:

// Two ways of getting the same data:

person.name // "Alice"

person["name"] // "Alice"

Nested Data

You can have arrays inside objects and vice versa. In fact, this happens all the time:

var myGameCharacter = {

name: "Gael, Ashen Knight",

race: "Half-Elf",

class: "Warrior",

level: 8,

alignment: "True Neutral",

stats: {

strength: 18,

dexterity: 14,

constitution: 16,

intelligence: 12,

wisdom: 13,

charisma: 10

},

skills: {

"Intimidation": "+7",

"Athletics": "+6",

"Perception": "+5"

},

inventory: {

weapon: "Eclipse Greatsword",

armor: "Cursed Knight Armor",

items: [

"Phantom Cloak",

"Sigil of the Forgotten"

]

},

backstory: "Eldred, known as the Ashen for surviving a pyre that consumed his clan, wanders the desolate lands of the Rusted Kingdom. Bearing the Eclipse Greatsword, a relic of his fallen people, he seeks vengeance against the spectral forces that haunt the ruins of his world."

};

This is actually how videogames work behind the scenes.

How would we get some of the nested data out of this?

In the object, myGameCharacter, you would access the items in the inventory by chaining together the property names using dot notation or a combination of dot and bracket notations:

// Accessing the character's alignment

var alignment = dndCharacter.alignment; // Returns "True Neutral"

// Accessing the intelligence stat

var intelligence = dndCharacter.stats.intelligence; // Returns 12

// Accessing the first item in the inventory items array

var firstInventoryItem = dndCharacter.inventory.items[0]; // Returns "Phantom Cloak"

A metaphor of a house is also nice to think about when learning about data structures:

Functions

Functions perform tasks. You define a function using the function keyword, give it a name, and then write the code it should run between curly braces {}. You can run this code by calling the function’s name.

function greet(name) {

return "Hello " + name + "!";

}

greet("Alice"); // runs the function with "Alice" as the value for name

We will talk more about functions in a future lecture.

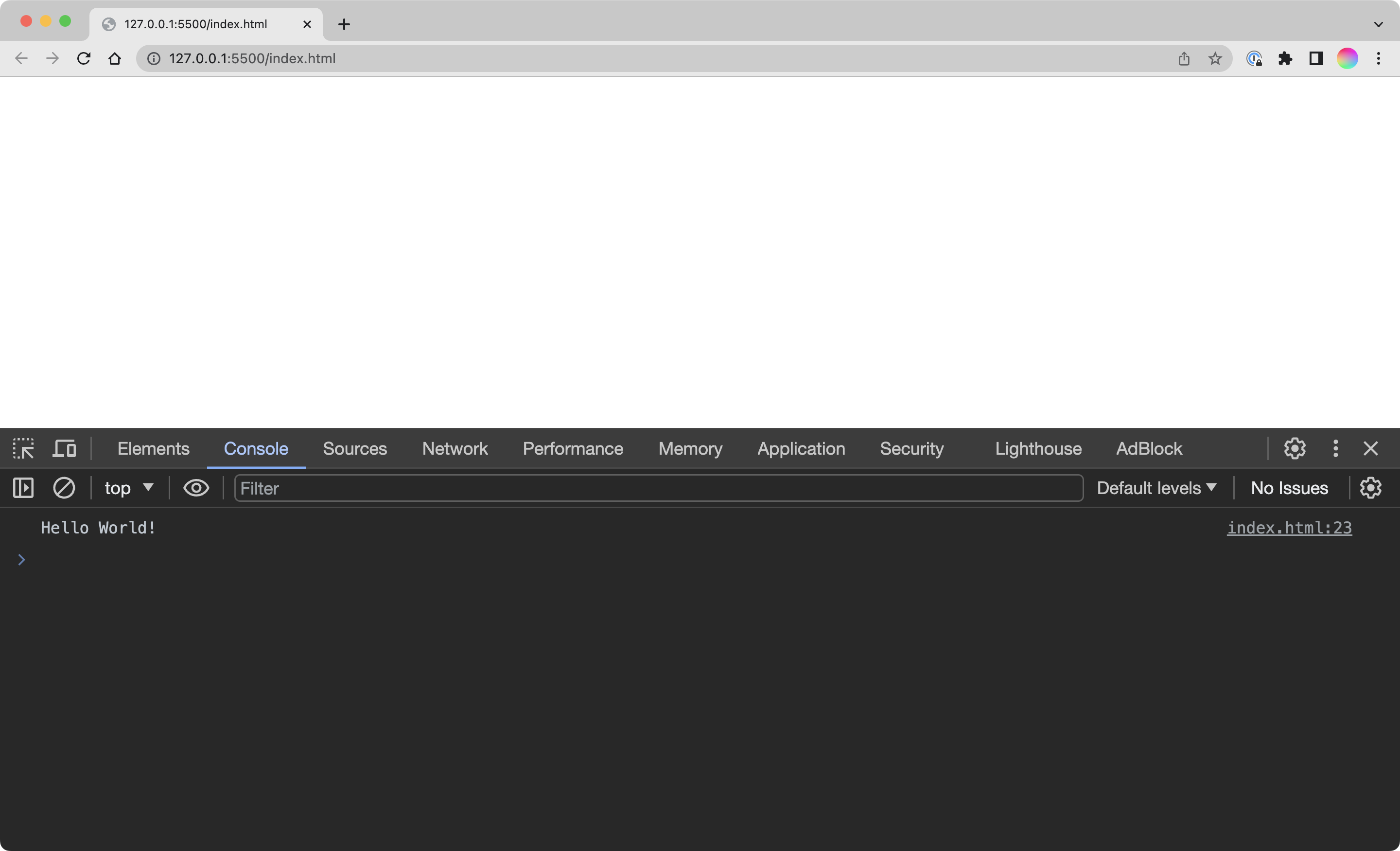

console.log()

How do we see what we’re doing, if it’s not on the page yet?

The console.log() method is a useful tool for debugging your JavaScript code. It prints a message to the browser’s console, which can be accessed by right-clicking on a web page and selecting “Inspect” (or “Inspect Element” in Firefox). The console is a great way to test your code and see if it’s working as expected:

console.log("Hello, World!");

So, going back to our earlier data example, we could use console.log() to actually see our data from JavaScript and make sure that it’s working properly:

JSON

JSON (JavaScript Object Notation) is a particular format for storing data, designed to be easy for both humans to read and write and machines to parse and generate. It’s particularly popular in web development for exchanging data between servers and web applications or websites.

Why JSON?

The need for JSON arose from the necessity to standardize data exchange across various systems and platforms. Before JSON, there were different methods to serialize data, which often led to compatibility issues.

Imagine that you have one particular way of structuring your data. That’s great if you’re the only person looking at it. But when you need to share this data, it is very inconvenient for the receipient to have to sort through it in your particular way. Now imagine your website gathers data from 10 different sources. If there’s no standard, this would take so long to figure out.

JSON provided a lightweight, text-based format that could be easily understood across different programming languages, making it an ideal choice for data interchange.

Structure

JSON is structured like a JavaScript object, with key-value pairs. In JSON, keys and string values must be enclosed in double quotes. Unlike JavaScript objects, JSON does not support functions or methods.

Here’s an example of JSON representing information about a movie. This would be in its own file, called something like movie-data.json:

{

"title": "Inception",

"director": "Christopher Nolan",

"year": 2010,

"actors": [

"Leonardo DiCaprio",

"Ellen Page",

"Tom Hardy"

]

}

You can of course, nest however much data you want:

{

"users": [

{

"name": "Alice",

"age": 30,

"friends": ["Bob", "Charlie"]

},

{

"name": "Dave",

"age": 40,

"friends": ["Eve"]

}

]

}

It is very similar to how we wrote objects earlier, but there is no var declaration or = assignment. To validate that your JSON is accurately formatted, you can use a “linter” like this: https://jsonlint.com/